Stress on Our Health

Stress plays a significant part in our lives in the western world today.

With long working hours, excessive pressure, sedate lifestyles and poor diet, stress has become a condition affecting all the major organs of the body, capable over the long-term of causing severe illness, even death.

Over 11 million days are lost at work a year because of stress at work.

Employers have a legal duty to protect employees from stress at work by doing a risk assessment and acting on it.

The basic chemical reaction within the body that leads to us feeling stressed has evolved as we have evolved. It is the same reaction that once kept us safe from predators and danger.

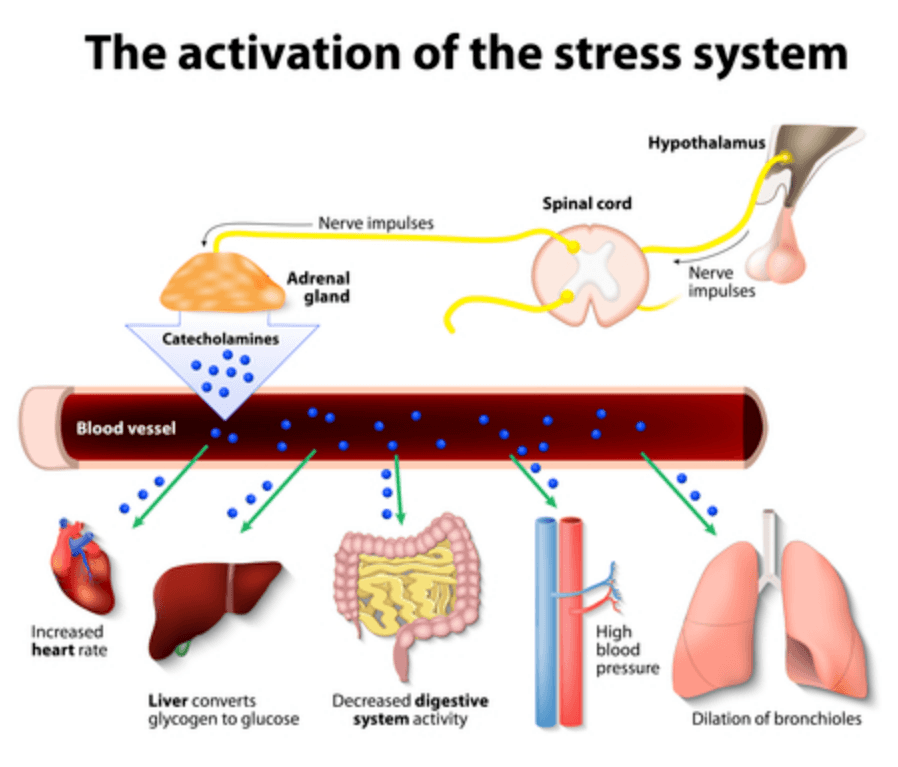

The reason the effect of stress has such a serious impact on our bodies is partly due to the rush of hormones; Cortisol and adrenaline (epinephrine), released when we feel under pressure. This then mobilises stored energy into the muscles, while at the same time increasing our heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate to prepare us for a 'fight or flight' response.

Structure of adrenaline

adrenaline is derived from tyrosine, an amino acid. Epinephrine is sometimes referred to as a catecholamine as it contains the catechol moiety. This is a part of the molecule that contains the group C6H4(OH)2.

Dopamine and adrenaline are also referred to as catecholamines. They too are synthesized from tyrosine and contain the catechol moiety.

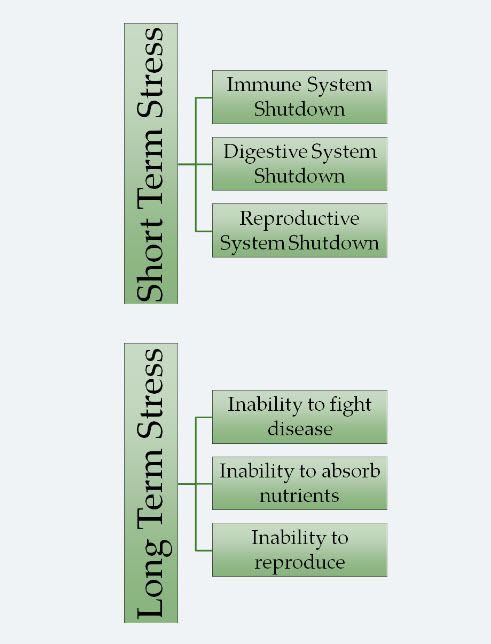

Meanwhile, the secondary functions; the digestive and reproductive systems, as well as the growth and immune systems are temporarily shut down to allow the body to focus on the threat.

This is exactly why we go weak at the knees when we are scared or stressed, then as we move away from the stressor the process begins to slow and then reverse.

When we are stressed long-term or stressed regularly such as in a poorly managed workplace, the process of becoming stressed in the short-term never really stops. It is always there at some level and the secondary functions of the body then cease working correctly.

This is when stress becomes physically damaging.

Examining the physical effects of stress on the body

The immune system is a collection of billions of cells, travelling through the bloodstream, moving in and out of tissues and organs, defending the body against foreign bodies (antigens), such as bacteria, viruses and cancerous cells.

The immune system is designed to defend the body against foreign or dangerous invaders.

Such invaders include

Microorganisms (commonly called germs, such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi)

Parasites (such as worms)

Cancer cells

Transplanted organs and tissues

To defend the body against these invaders, the immune system must be able to distinguish between

What belongs in the body (self)

What does not (nonself or foreign)

Antigens are any substances that are identified as nonself—particularly if they are perceived as dangerous (for example, if they can cause disease) and that can stimulate an immune response in the body.

Antigens may be contained within or on bacteria, viruses, other microorganisms, parasites, or cancer cells. Antigens may also exist on their own—for example, as food molecules or pollen.

Physical barriers

The first line of defense against invaders is mechanical or physical barriers:

The skin

The cornea of the eyes

Membranes lining the respiratory, digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts

As long as these barriers remain unbroken, many invaders cannot enter the body. If a barrier is broken—for example, if extensive burns damage the skin—the risk of infection is increased.

In addition, the barriers are defended by secretions containing enzymes that can destroy bacteria. Examples are sweat, tears in the eyes, mucus in the respiratory and digestive tracts, and secretions in the vagina.

White blood cells

The next line of defense involves white blood cells (leukocytes) that travel through the bloodstream and into tissues, searching for and attacking microorganisms and other invaders. The main types of immune cells are white blood cells, of which there are two types - lymphocytes and phagocytes.

This defense has two parts:

- Innate immunity

- Acquired immunity

Innate (natural) immunity does not require a previous encounter with a microorganism or other invader to work effectively.

It responds to invaders immediately, without needing to learn to recognize them. Several types of white blood cells are involved:

- Phagocytes ingest invaders. Phagocytes include macrophages, neutrophils, monocytes, and dendritic cells.

- Natural killer cells are formed ready to recognize and kill cancer cells and cells that are infected with certain viruses.

- Some white blood cells (such as basophils and eosinophils) release substances involved in inflammation, such as cytokines, and in allergic reactions, such as histamine. Some of these cells can destroy invaders directly.

In acquired (adaptive or specific) immunity, white blood cells called lymphocytes (B cells and T cells) encounter an invader, learn how to attack it, and remember the specific invader so that they can attack it even more efficiently the next time they encounter it.

Acquired immunity takes time to develop after the initial encounter with a new invader because the lymphocytes must adapt to it.

However, thereafter, response is quick. B cells and T cells work together to destroy invaders.

To be able to recognize invaders, T cells need help from cells called antigen-presenting cells. These cells ingest an invader and break it into fragments.

There are two types of lymphocytes:

B cells - which produce antibodies which are released into the fluid surrounding the body's cells to destroy the invading viruses and bacteria.

T cells - if the invader gets inside a cell, these (T cells) lock on to the infected cell, multiply and destroy it.

When we're stressed, the immune system's ability to fight off antigens is reduced. That is why we are more susceptible to infections.

The stress hormone corticosteroid can suppress the effectiveness of the immune system (e.g. lowers the number of lymphocytes).

Stress can also lead to headaches, infectious illness (e.g. flu), cardiovascular disease, diabetes, asthma and gastric ulcers.

Stress response also influences our digestive system. During stress, digestion is inhibited which may affect the health of our digestive system long-term and lead to ulcers. Adrenaline released during a stress response may also cause ulcers.

Stress responses increase the strain on our circulatory system due to the increase in heart rate etc. Stress can also affect the immune system by raising blood pressure.

Hypertension (consistently raised blood pressure over several weeks) is a major risk factor in coronary heart disease (CHD) However, CHD can also be caused by eating too much salt or drinking too much coffee or alcohol.

Stress also produces an increase in blood cholesterol levels, through the action of adrenaline and noradrenaline on the release of free fatty acids. This produces a clumping together of cholesterol particles, leading to clots in the blood and in the artery walls and occlusion of the arteries.

In turn, raised heart rate is related to a more rapid build-up of cholesterol on artery walls. High blood pressure results in small lesions on the artery walls, and cholesterol tends to get trapped in these lesions.

Stress can also have an indirect effect on illness as it is associated with all manner of bad habits (coping strategies), for example, smoking, drinking alcohol to excess, poor diet due to lack of time, lack of exercise for the same reason, lack of sleep etc.

All these activities are likely to have an adverse effect on a person's health so could cause some of the ill-effects attributed to stress per se.

Stress and Immune Function

Short-term suppression of the immune system is not dangerous. However, chronic suppression leaves the body vulnerable to infection and disease.

A current example of this is AIDS - Acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Here the immune system is suppressed leaving the sufferer vulnerable to fatal illness.

Stress responses increase strain on the circulatory system due to increased heart rate etc. This may increase a person's risk of developing disorders of the heart and circulation e.g. coronary heart disease (CHD).

Individuals with type A personality have a greater risk of developing CHD.

Stress responses also influence the digestive system.

During stress, digestion is inhibited.

After stress, digestive activity increases.

Long-term this may affect the health of the digestive system and cause gastric ulcers.

Research: Case study

A 1984 study examined the effects of stress on 75 first year medical students (49 males and 26 females), all of whom were volunteers.

Blood samples were taken: (a) one month before their final examinations (relatively low stress), and (b) during the examinations (high stress)

Immune functioning was assessed by measuring T cell activity in the blood samples.

The students were also given questionnaires to assess psychological variables such as life events and loneliness.

The blood samples taken from the first group (before the exam) contained more t-cells compared with blood samples taken during the exams.

The volunteers were also assessed using behavioural measures. On both occasions they were given questionnaires to assess psychiatric symptoms, loneliness and life events. This was because there are theories which suggest that all three are associated with increased levels of stress.

It was found that immune responses were especially weak in those students who reported feeling most lonely, as well as those who were experiencing other stressful life events and psychiatric symptoms such as depression or anxiety. Stress (of the exam) reduced the effectiveness of the immune system.

However, even after further studies examining the link between stress and illness it is still difficult to prove a causal link. We don't know for sure if stress causes illness or if being III makes you more prone to stress.