- in Mental Health by Tony

Could Artificial Intelligence Treat Mental Health?

Mental illness is a growing concern across the world. With advancements in technology, could artificial intelligence (AI) provide a solution to this problem?

Artificial intelligence has already been used in various applications, from self-driving cars to virtual assistants. However, recently, artificial intelligence has gained interest in the mental health field.

This article will explore this concept further.

More...

There was an incredible explosion of need, especially in the wake of Covid-19, with soaring rates of anxiety and depression and insufficient practitioners, said Dr Olusola A. Ajilore, professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

“This kind of technology may serve as a bridge. It’s not meant to replace traditional therapy, but it may be an important stop-gap before somebody can seek treatment.”

Over half of all mental illnesses remain untreated, leading to depreciating mental conditions, chronic physical health concerns, job stability issues, homelessness, trauma, and suicide.

It’s a tragic fact that suicide is now the fourth leading cause of death among 15 to 29-year-olds worldwide. This inevitably leads to growing pressure on already-stretched healthcare and therapeutic services, which have become increasingly difficult for many to access.

Many undiagnosed individuals suffering from mental health conditions end up seeking treatment in emergency rooms or with their primary care physicians, and Quartet’s platform, identifies and flags potential mentally ill conditions. Surprisingly, people with any mental health conditions are six times more likely to visit their ER than the general population.

Quartet’s platform utilises advanced technology, data analysis, and integrated care models to identify individuals at risk for mental health conditions. By partnering with healthcare providers, payers, and employers, Quartet facilitates a collaborative approach to mental health care.

The platform also provides patients with resources and tools for self-management, enabling them to participate in their mental well-being actively.

While Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a rapidly developing field, it is still in its early stages when treating mental illness. Some studies and research have been conducted on using Artificial Intelligence to treat mental illness, such as using chatbots for therapy sessions and analysing behaviour patterns to predict and prevent mental health crises. However, Artificial Intelligence should not replace traditional therapy or medication for treating mental illness.

It is important to note that mental health treatment needs to consider the individual’s unique experiences and perspectives, something that AI may not fully comprehend. Nevertheless, Artificial Intelligence can also play a valuable role in improving mental health care by aiding in diagnosis and identifying potential issues early on.

Overall, while Artificial Intelligence has the potential to be a valuable mechanism in mental health care, it is essential to proceed with caution and not depend solely on technology for treating such complex issues.

This revolutionary technology is already changing lives and improving patient outcomes for various mental health conditions. Let’s explore some of the ways it is being used.

Mental health patients increasingly benefit from chatbots, which provide advice and communication during treatment. These chatbots assist with symptom management and recognise keywords that may necessitate contacting a human mental healthcare professional.

Woebot is a prime example of a therapeutic chatbot that adapts to users’ personalities and guides them through various therapies and exercises for coping with different conditions.

Woebot is a Facebook-integrated bot [device/software that executes commands] whose Artificial Intelligence is “versed in cognitive behavioural therapy” a treatment that aims to change patterns in people’s thinking.

Dr Alison Darcy developed the AI-powered chatbot as a technological tool to provide individuals with mental health support and assistance in 2017. The chatbot utilises artificial intelligence algorithms to simulate human-like conversations and understand and respond to users’ queries or concerns.

The chatbot can use advanced natural language processing techniques to engage in personalised conversations and promptly provide users with appropriate resources, guidance, and emotional support.

Woebot is one of several successful phone-based chatbots, some explicitly aimed at mental health, others designed to provide entertainment, comfort, or a sympathetic conversation.

Today, millions of people talk to programs and apps such as Happify, which encourages users to “break old patterns,” and replica, an “Artificial Intelligence companion” that is “always on your side,” serving as a friend, a mentor, or even a romantic partner.

Tess, is another chatbot, that provides free emotional support around the clock for individuals experiencing anxiety and panic attacks. It is available on-demand and can be accessed anytime to help cope with these conditions effectively.

A new pilot study led by the University of Illinois, Chicago was the first to test an Artificial Intelligence voice-based virtual coach for behavioural therapy and found changes in patients’ brain activity along with improved depression and anxiety symptoms after using Lumen.

This Artificial Intelligence voice assistant delivered a form of psychotherapy and lumen, which also operates as a skill in the Amazon Alexa application, was developed by Ajilore and senior study author Dr. Jun Ma. The University of Illinois Chicago team said the results, published in the Journal Translational Psychiatry, offer encouraging evidence that virtual therapy can play a role in filling the gaps in mental health care.

Peter Foltz, a research professor at the Institute of Cognitive Science and his vision of a Brave New World scenario predicts a future based on artificial intelligence, advanced robotics, and biotechnology to create self-sustaining global societies.

It proposes a world where mortality rates are low, labour is automated, and digital connectivity is ubiquitous.

As Foltz stated, as patients “often need to be monitored with frequent clinical interviews by trained professionals” insufficient clinicians and the App can assist in monitoring these subtle changes in their mental health whilst notifying the patient’s doctor to check in on them.

In 2013, the U.K.'s National Health Service (NHS) partnered with ieso, a digital-health company, to expand its mental-health treatment. The goal was to provide cognitive behavioural therapy through text chat, allowing therapists to reach more patients.

The best use for Artificial Intelligence in health care, doctors say, is to ease the heavy burden of documentation that takes them hours a day and contributes to burnout. ChatGPT-style artificial intelligence is coming to health care, A prime target will be to ease the crushing burden of digital paperwork that physicians must produce, typing lengthy notes into electronic medical records required for treatment, billing and administrative purposes. Doctors are also using chatbots to communicate more effectively with some patients.

Brave New World

On the other hand, Aldous Huxley classic novel “Brave New World,” was published in 1932. The book depicts a dystopian society in the future where technological advancements and scientific methods have completely reshaped human life.

With Huxley’s vision of a “Brave New World,” it portrays a society controlled and manipulated by a powerful government through advanced technology, conditioning, and genetic engineering.

Let us be clear, Artificial intelligence (AI) can benefit society significantly, but it poses certain dangers and risks. Overall, the portrayal of artificial intelligence in films like:

- The Terminator

- The Matrix

- Westworld

Or even Steven Spielberg science fiction AI film in 2001, explores the concept of artificial intelligence and its impact on society. The story follows the journey of a young robot named David, who desires to become a real boy and seeks love and acceptance.

Some of you may also be considering Mr Data on the starship Enterprise, who also wanted to become human. At what point does science fiction become science fact.

However, with literature spanning decades reflecting society’s fascination with the possibilities, dangers, and ethical considerations associated with this technological specialisation becoming a reality is now starting to make a lot of people nervous.

Someone may say the “writing is on the wall”, allowing us to explore and contemplate the potential future of Artificial intelligence while raising important questions about its impact on our lives or future.

Machine learning

One approach commonly used by computational psychiatrists is the application of machine learning to clinical populations. Machine learning is a system that can learn and improve from experience without being explicitly programmed.

This implementation of Artificial Intelligence to diagnose, predict and treat mental health conditions is an exciting and emerging field that could help relieve the burden of mental illness for individuals suffering and our healthcare system.

Henry Nasrallah, a psychiatrist at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center who has also written about artificial intelligence, claims that analysing speech, for example, if the patient is talking in a monotone voice, could this be an indication of depression; fast speech can point to mania, and disjointed word choice can be connected to schizophrenia.

The human voice carries a wealth of information regarding a speaker, its physical characteristics, state of mind and health. When these traits are pronounced enough, a human clinician might pick up on them—but AI algorithms, Nasrallah says, could be trained to flag signals and patterns too subtle for humans to detect.

Voice acoustics allow classifying autism spectrum disorder with high accuracy. Voice production involves the entire brain and is under the influence of both autonomic and somatic nervous systems. Autism spectrum disorder is characterized by impaired functioning of both somatic and autonomic nervous systems, and these impairments have consequences in their vocal production.

Early research efforts have used artificial intelligence to predict individual outcomes by analysing how people communicate. Bedi and colleagues conducted some research in 2015 that involved using Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) to predict the onset of psychosis in youths.

In this study, individuals deemed at high risk for developing psychosis were interviewed regularly, and this was deemed to be 100% successful. Improving the capacity to predict psychosis among high-risk populations would have important ramifications for early identification and preventive intervention.

John Pestian, a computer scientist who specialises in the analysis of medical data, first started using machine learning to study mental illness when he joined the faculty of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

In graduate school, he built statistical models to improve care for patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery. At Cincinnati Children’s, which operates the largest paediatric psychiatric facility in the country, he was shocked by how many young people came in after trying to end their own lives. He wanted to know whether computers could determine who was at risk of self-harm.

There are several different types of bots that are being used in healthcare today. Here are a few examples:

1. Appointment bots: These bots assist patients in scheduling appointments with healthcare providers. They can also help with rescheduling or cancelling appointments if needed. This type of bot is commonly found on healthcare organisation websites or mobile apps.

2. Symptom checker bots: These bots help users determine the possible cause of their symptoms by asking a series of questions. They provide information on potential diagnoses and suggest when it may be necessary to seek medical attention. This type of bot can be found on healthcare websites or as standalone apps.

3. Medication reminder bots: These bots send reminders to patients to take their medications at the prescribed times. They can be programmed to customize reminders based on individual needs, such as specific medications, dosage, and frequency. This type of bot is often integrated into healthcare mobile apps.

4. Mental health support bots: These bots offer support and resources for individuals experiencing mental health issues. They can provide coping strategies, mindfulness exercises, and access to mental health professionals when needed. Mental health support bots are typically found on mental health websites or apps.

5. Health monitoring bots: These bots collect and analyse data from wearable devices or other health monitoring tools. They can track vital signs, physical activity, sleep patterns, and more. The information gathered can be used by healthcare professionals to monitor and manage patients' health conditions remotely.

It's important to note that while bots can be helpful tools in healthcare, they should not replace the expertise and personalized care provided by healthcare professionals. They are designed to assist and enhance the healthcare experience, but should not be solely relied upon for medical advice or treatment.

American Association of Suicidology

Pestian contacted Edwin S Shneidman, a clinical psychologist who’d founded the American Association of Suicidology. Shneidman gave him hundreds of suicide notes that families had shared with him, and Pestian expanded the collection into what he believes is the world’s largest. During one of our conversations, he showed me a note written by a young woman.

On one side was an angry message to her boyfriend, and on the other, she addressed her parents: “Daddy, please hurry home”. Mom, I’m so tired. Please forgive me for everything. Studying the suicide notes, Pestian noticed patterns. The most common statements were not expressions of guilt, sorrow, or anger, but instructions:

Make sure your brother repays the money I lent him; the car is almost out of gas; careful, there’s cyanide in the bathroom. He and his colleagues fed the notes into a language model

—an artificial intelligence system that learns which words and phrases tend to go together—and then tested its ability to recognise suicidal ideation in statements that people made. The results suggested that an algorithm could identify “the language of suicide.”

Next, Pestian turned to audio recordings taken from patient visits to the hospital’s emergency room. With his colleagues; he developed software to analyse not just the words people spoke but the sounds of their speech.

The team found that people experiencing suicidal thoughts sighed more and laughed less than others. When speaking, they tended to pause longer and shorten their vowels, making words less intelligible; their voices sounded breathier, and they expressed more anger and less hope.

In the largest trial of its kind, Pestian’s team enrolled hundreds of patients, recorded their speech, and used algorithms to classify them as suicidal, mentally ill but not suicidal, or neither.

About eighty-five per cent of the time, his Artificial Intelligence (AI) model came to the same conclusions as human caregivers—making it potentially useful for inexperienced, overbooked, or uncertain clinicians.

A few years ago, Pestian and his colleagues used the algorithm to create an app called Sam, which could be employed by school therapists. They tested it in some Cincinnati public schools.

Ben Crotte, then a therapist treating middle and high school, was among the first to try it. When asking students for their consent, “I was very straightforward,” Crotte told me. “I’d say, this application basically listens in on our conversation, records it, and compares what you say to what other people have said to identify who’s at risk of hurting or killing themselves.”

One afternoon, Crotte met with a high-school freshman who was struggling with severe anxiety. During their conversation, she questioned whether she wanted to keep on living. If she was actively suicidal, then Crotte had an obligation to inform a supervisor, who might take further action, such as recommending that she be hospitalised.

After talking more, he decided that she wasn’t in immediate danger—but the Artificial Intelligence came to the opposite conclusion. On the one hand, I thought, This thing really does work—if you’d just met her, you’d be pretty worried, Crotte said. “But there were all these things I knew about her that the app didn’t know.”

The girl had no history of hurting herself, no specific plans to do anything, and a supportive family. I asked Crotte what might have happened if he had been less familiar with the student or less experienced.

“It would definitely make me hesitant to just let her leave my office,” he told me. “I’d feel nervous about the liability of it. You have this thing telling you someone is high-risk, and you’re just going to let them go?”

Wearables in the field of mental health

Wearables in the mental health field offer a unique and proactive approach to support individuals in managing their emotional well-being. By continuously monitoring bodily signals such as heart rate, physical activity, and sleep patterns, wearables like Biobeat can assess the user’s mood and cognitive state.

This data is then compared with aggregated information from other users to identify potential warning signs and intervene when necessary. This proactive approach allows individuals to adjust their behaviour or seek assistance from healthcare services before their mental health deteriorates. Wearables in mental health provide valuable insights and empower individuals to take control of their emotional well-being in a timely manner.

Considering the growing wearable technology trend, one in five Americans owning a smartwatch or activity tracker is not surprising. These devices have become popular because they provide accurate data about various aspects of our lives, such as fitness and health.

However, the potential of wearable technology goes beyond physical health, as it is also being developed for mental health care. These dedicated wearable devices aim to gather data specifically related to mental well-being, allowing individuals and healthcare professionals to track and monitor mental health conditions more effectively.

By providing better quality data than a smartphone, these devices offer a promising opportunity to improve mental health care and support individuals in managing and addressing their mental well-being.

John Carroll, an experimental psychologist and director of the Center for Human-Computer Interaction at Penn State University, notes that wearable technology is not for everyone and won’t suffice for people with severe symptoms. It’s beneficial to distinguish the severe cases from the non-serious ones,

Obviously, the most promising device is the smartphone, and there’s a good reason why the smartphone is the chief conduit of portable technology, even though it’s not a perfect tool for gathering data.

Roughly half of people who own a smartwatch, whereas the most common consumer wearable could end up in a drawer after acquiring them. The smartphone, on the other hand, is ubiquitous. Especially among younger people, when a smartphone is not on the user’s person, chances are that person is either in the shower or bed sleeping.

Wrist-worn accelerometers, like those in smartwatches, can help detect Parkinson's Disease before a clinical diagnosis is available, according to a new study.

Most smartwatches contain a sensor that measures the acceleration of a moving body, known as an accelerometer. A 2021 study showed that wrist-worn accelerometers could detect Parkinson’s with high accuracy.

Loss of sensitive information and medical disclosure

There are concerns, says Timothy Aungst, associate professor of pharmacy practice at the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences has moral and ethical considerations concerning the data being gathered, and who has the right to access such data.

Leading to the possibility for your data to be leaked or breached in a way that causes actual psychological or financial harm to vulnerable individuals.

AI delivering therapeutic therapy

Person-centred therapy, also known as Rogerian therapy or client-based therapy, employs a non-authoritative approach that allows clients to take more of a lead in sessions such that, in the process, they discover their own solutions.

Joseph Weizenbaum, a computer scientist at M.I.T., created a computer program called Eliza in the nineteen-sixties. It was designed to simulate Rogerian therapy, in which the patient directs the conversation, and the therapist often repeats her language back to them:

User: My boyfriend made me come here.

Eliza: Your boyfriend made you come here.

User: He says I’m depressed much of the time.

Eliza: I am sorry to hear you are depressed.

User: It’s true. I am unhappy.

Eliza: Do you think coming here will help you not to be unhappy?

Weizenbaum made Eliza a satire by naming it after Eliza Doolittle, the poor Cockney flower girl who faked-it-till-you-make-it heroine of George Bernard Shaw’s “Pygmalion,” thereby creating a therapeutic illusion despite having “no memory” and “no processing power,”

He doubted that computers could simulate meaningful human interaction. But he was alarmed, therefore, when many people who tried the program found it helpful and captivating. His secretary asked him to leave the room, so she could spend time alone with Eliza.

Worse, doctors saw it as a potentially transformative tool. “Several hundred patients an hour could be handled by a computer system designed for this purpose,” three psychiatrists wrote in The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease in 1966.

“The human therapist, involved in the design and operation of this system, would not be replaced, but would become a much more efficient person since his efforts would no longer be limited to the one-to-one patient-therapist ratio as now exists.”

Weizenbaum became an outspoken critic of artificial intelligence.

“But the genie was out of the bottle,” Brian Christian, who chronicled the episode in his book “The Most Human Human,” told me. A few years later, a Stanford psychiatrist named Kenneth Colby created Parry.

This program attempted to simulate the language of a person with paranoid schizophrenia to train students before they cared for actual patients. Psychiatrists gave transcripts of therapy sessions and often couldn’t tell the difference between Parry and humans; in this narrow sense, the chatbot passed the Turing test.

In 1972, Parry and Eliza met up for a therapy session:

Parry: Do you know anything about bookies?

Eliza: What makes you think I know anything about bookies?

Parry: A bookie didn’t pay me off once.

Eliza: What does that suggest to you?

Parry: I beat up the bookie who did not pay off, and I thought he might use his friends in the underworld to get even with me.

Over time, programmers developed Jabberwacky, Dr. Sbaitso, and Alice (the Artificial Linguistic Internet Computer Entity). Exchanges with these chatbots were often engaging, sometimes comical, and occasionally nonsensical.

But the idea that computers could serve as human confidants, expanding therapy’s reach beyond the limits of its overworked practitioners, persisted through the decades.

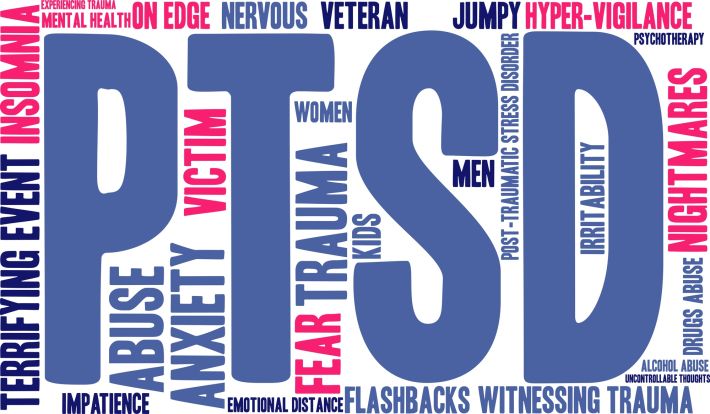

Algorithmic psychiatry involves many practical complexities. The Veterans Health Administration, a division of the Department of Veterans Affairs, may be the first large healthcare provider to confront them.

A few days before Thanksgiving 2005, a twenty-two-year-old Army specialist named Joshua Omvig returned home to Iowa after an eleven-month deployment in Iraq, showing signs of post-traumatic stress disorder; a month later, he died by suicide in his truck.

In 2007, Congress passed the Joshua Omvig Veterans Suicide Prevention Act, the first federal legislation to address a long-standing epidemic of suicide among veterans. Its initiatives—a crisis hotline, a campaign to destigmatise mental illness, mandatory training for V.A. staff—were no match for the problem.

Each year, thousands of veterans die by suicide—many times the number of soldiers who die in combat. A team that included John McCarthy, the V.A.’s director of data and surveillance for suicide prevention, gathered information about V.A. patients, using statistics to identify possible risk factors for suicide, such as chronic pain, homelessness, and depression.

Their findings were shared with V.A. caregivers, but between this data, the evolution of medical research, and the sheer quantity of patients’ records, “clinicians in care were getting just overloaded with signals,” McCarthy told me.

In 2013, the team started working on a program that would analyse V.A. patient data automatically, hoping to identify those at risk. In tests, the algorithm they developed flagged many people who had gone unnoticed in other screenings—a signal that it was “providing something novel,” McCarthy said.

The algorithm eventually came to focus on sixty-one variables. Some are intuitive: for instance, the algorithm is likely to flag a widowed veteran with a serious disability who is on several mood stabilisers and has recently been hospitalised for a psychiatric condition.

But others are less obvious: having arthritis, lupus, or head-and-neck cancer; taking statins or Ambien; or living in the Western U.S. can also add to a veteran’s risk.

In 2017, the V.A. announced an initiative called reach vet, which introduced the algorithm into clinical practice throughout its system. Each month, it flags about six thousand patients, some for the first time; clinicians contact them and offer mental-health services, ask about stressors, and help with access to food and housing.

Inevitably, there is a strangeness to the procedure: veterans are being contacted about ideas they may not have had. The V.A. had considered being vague—just saying, You’ve been identified as at risk for a bunch of bad outcomes, McCarthy told me. But, ultimately, we communicated rather plainly, You’ve been identified as at risk for suicide. We wanted to check in and see how you’re doing.

Patient compliance

Ensuring patient compliance is a major challenge in treating mental health conditions. It involves making sure patients take medication and attend therapy sessions as prescribed.

AI can help predict when a patient might become non-compliant. It can then send reminders or alert healthcare providers for manual interventions.

Methods of communication include chatbots, SMS, automated calls, and emails.

In Conclusion

While Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) is a rapidly developing field, it is still in its early stages when it comes to treating mental illness.

Some studies and research have been conducted on using Artificial Intelligence to treat mental illness, such as using chatbots for therapy sessions and analysing patterns of behaviour to predict and prevent mental health crises. However, artificial intelligence should not replace traditional therapy or medication for treating mental illness.

It is important to note that mental health treatment needs to take into account the individual’s unique experiences and perspectives, something that Artificial Intelligence may not be able to comprehend fully.

Nonetheless, A.I. can also play a valuable role in improving mental health care by aiding in diagnosis and identifying potential issues early on. Overall, while Artificial Intelligence has the potential to be a useful tool in mental health care, it is essential to proceed with caution and not depend solely on technology for treating such complex issues.